Landscape architecture is a multifaceted profession that seamlessly blends art and science to design, plan, and manage outdoor spaces. It’s far more than just planting trees; it encompasses the thoughtful arrangement of natural and constructed elements to create environments that are both beautiful and functional, sustainable, and socially impactful. From sprawling urban parks and revitalized waterfronts to intimate residential gardens and large-scale regional planning, crafting outdoor spaces involves a deep understanding of ecology, urbanism, human behavior, and aesthetic principles. This isn’t merely about aesthetics; it’s about shaping the physical world to enhance human well-being and protect the planet, leaving an enduring mark on our built and natural environments.

The Evolution of Outdoor Design

The practice of shaping outdoor environments for human use and enjoyment has roots stretching back millennia, evolving with civilizations and reflecting changing societal values, technological capabilities, and aesthetic preferences.

A. Ancient Origins and Early Gardens:

* Mesopotamia and Egypt: Early evidence of planned landscapes for practical purposes, such as irrigation channels for agriculture, and for aesthetic and symbolic reasons, like the Hanging Gardens of Babylon (though their existence is debated) and enclosed temple gardens in Egypt. These gardens often served religious or royal purposes, emphasizing order and control over nature.

* Persian Gardens: Characterized by geometric layouts, water features (canals, fountains), and shady areas, often enclosed and symbolizing paradise. These highly influential designs spread across the Islamic world.

* Classical Greece and Rome: While less focused on elaborate gardens for public use, Greek landscapes often incorporated sacred groves and public agora. Roman gardens were more integrated with villas, featuring courtyards, frescoes depicting nature, and elements like topiary, reflecting a more leisure-oriented approach.

B. Medieval and Renaissance Eras:

* Medieval Gardens: Primarily functional (kitchen gardens, medicinal herbs) within monasteries and castles, offering practicality and spiritual contemplation. Formal elements were typically enclosed within walls.

* Renaissance Gardens (Italy): A revival of classical ideals, emphasizing geometry, symmetry, dramatic terracing, water features (fountains, grottoes), and a strong visual connection between the architecture of a villa and its surrounding landscape (e.g., Villa d’Este, Boboli Gardens). These gardens were spectacles of power and order.

* Baroque Gardens (France): The epitome of grand, symmetrical, and expansive design, most famously exemplified by the Gardens of Versailles. Characterized by vast parterres (ornamental garden beds), long axes, canals, and controlled nature, reflecting absolute monarchy’s power over the landscape. André Le Nôtre was a key figure.

C. The English Landscape Movement and Beyond:

* English Landscape Gardens (18th Century): A radical departure from formal, symmetrical designs. Inspired by picturesque paintings, these gardens aimed to create idealized, “natural” landscapes with winding paths, rolling hills, scattered trees, and lakes, often featuring classical follies or ruins. Key figures include Capability Brown and Humphry Repton.

* Urban Parks (19th Century): Rapid industrialization led to overcrowded, polluted cities. The need for public green spaces for recreation, health, and social amelioration sparked the creation of large urban parks, particularly in North America and Europe. Frederick Law Olmsted, designer of Central Park, was a pivotal figure, pioneering the integration of social function with ecological design.

* Arts and Crafts Movement (Late 19th – Early 20th Century): Emphasized naturalistic planting, local materials, and a sense of craftsmanship, often integrating gardens more intimately with domestic architecture. Gertrude Jekyll was a prominent figure.

D. Modernism and Contemporary Landscape Architecture:

* Modernist Landscape: Inspired by abstract art and new materials, focusing on clean lines, functionalism, and minimalist aesthetics. Brazilian landscape architect Roberto Burle Marx revolutionized tropical modernism with bold, abstract forms and native plants.

* Post-War Public Landscapes: After WWII, landscape architecture played a crucial role in urban renewal, creating civic plazas, housing landscapes, and recreational facilities.

* Ecological Turn (Late 20th Century): Growing environmental awareness led to a focus on ecological principles, sustainability, native planting, stormwater management, and restoring degraded landscapes. This marked a significant shift towards more environmentally responsible design.

* Contemporary Practice: Today, landscape architecture embraces diverse approaches, from ecological restoration and climate-resilient design to highly urban interventions, placemaking, and the integration of smart technologies.

Core Principles and Disciplines

Landscape architecture is a multidisciplinary field that integrates knowledge from environmental science, horticulture, civil engineering, urban planning, and visual arts to create holistic and impactful designs.

A. Aesthetic Design and Form:

* Composition and Balance: Arranging elements (plants, water, hardscape) to create visual harmony, rhythm, and interest. Understanding scale, proportion, and visual weight.

* Color, Texture, and Scent: Using plant palettes and materials to evoke specific moods, stimulate the senses, and create year-round appeal.

* Light and Shadow: Designing with the movement of light throughout the day and year to create dramatic effects and define spaces.

* Spatial Definition: Using physical elements (walls, hedges, trees) to create distinct outdoor rooms, pathways, and transitions, guiding human movement and perception.

* Human Experience: Creating spaces that evoke positive emotions, encourage interaction, provide comfort, and cater to diverse human activities.

B. Ecological and Environmental Science:

* Site Analysis: Thorough understanding of existing site conditions, including topography, soil composition, hydrology, climate, sun exposure, and existing flora and fauna.

* Ecosystem Services: Designing landscapes that provide ecological benefits such as stormwater management, air and water purification, biodiversity support, and carbon sequestration.

* Native Planting: Utilizing indigenous plant species that are adapted to the local climate, require less water and maintenance, and support local wildlife.

* Sustainable Materials: Specifying environmentally friendly, recycled, or locally sourced materials to reduce embodied energy and environmental impact.

* Climate Resilience: Designing landscapes that can withstand and adapt to the impacts of climate change, such as extreme heat, heavy rainfall, or drought, and mitigate urban heat island effects.

C. Functionality and Human Behavior:

* Programmatic Needs: Designing spaces that effectively serve their intended functions, whether it’s active recreation, quiet contemplation, social gathering, or ecological restoration.

* Accessibility: Ensuring that landscapes are accessible and usable by people of all abilities, adhering to universal design principles.

* Wayfinding: Designing clear and intuitive pathways, signage, and visual cues to guide users through a space.

* Safety and Security: Incorporating design elements that enhance safety, reduce crime (e.g., CPTED – Crime Prevention Through Environmental Design), and provide comfortable public spaces.

* Social Interaction: Creating opportunities for community engagement, fostering social connections, and promoting a sense of place.

D. Technical Knowledge and Construction:

* Grading and Drainage: Designing site contours and drainage systems to manage stormwater runoff, prevent erosion, and create usable landforms.

* Horticulture and Planting Design: In-depth knowledge of plant species, their growth habits, cultural requirements, and how to combine them for aesthetic and ecological effect.

* Irrigation Systems: Designing efficient irrigation systems that minimize water waste.

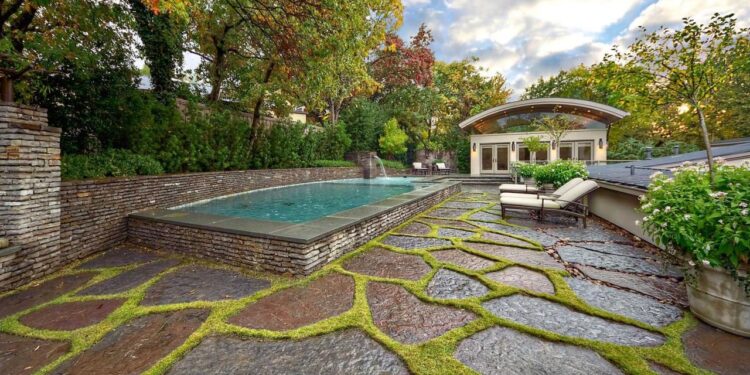

* Hardscape Design: Designing and specifying pavements, walls, stairs, seating, lighting, and other constructed elements.

* Cost Estimation and Project Management: Managing budgets, timelines, and coordinating with contractors and other professionals (e.g., architects, engineers).

* Regulations and Codes: Understanding and complying with local zoning laws, building codes, environmental regulations, and accessibility standards.

Typologies of Practice

Landscape architects apply their diverse skills across a vast array of project types, from small-scale private gardens to vast regional planning initiatives.

A. Urban Landscapes:

* Public Parks and Plazas: Designing iconic green spaces that serve as vital civic infrastructure, providing recreation, relaxation, and community gathering points (e.g., Millennium Park, Chicago; High Line, New York).

* Streetscapes and Pedestrian Zones: Enhancing urban vitality through street design, pedestrian pathways, urban furniture, and green infrastructure that promotes walkability and livability.

* Waterfront Redevelopment: Transforming derelict industrial waterfronts into vibrant public spaces, often incorporating ecological restoration and flood protection measures.

* Transit-Oriented Development (TOD): Designing green spaces and public realm elements around transportation hubs to create sustainable, walkable communities.

* Rooftop Gardens and Green Walls: Bringing nature into dense urban environments, improving air quality, managing stormwater, and enhancing aesthetics.

B. Residential Landscapes:

* Private Gardens: Designing custom outdoor spaces for homeowners, ranging from small urban courtyards to expansive suburban estates, tailored to individual preferences and lifestyle.

* Multi-Family Housing: Designing shared green spaces, courtyards, and amenities for apartment complexes and condominiums, enhancing resident quality of life.

* Sustainable Residential Design: Incorporating native plants, permeable paving, rainwater harvesting, and edible gardens to create environmentally friendly home landscapes.

C. Commercial and Institutional Landscapes:

* Corporate Campuses: Designing attractive and functional outdoor spaces for office parks, often incorporating green infrastructure, walking trails, and amenity zones to enhance employee well-being and corporate image.

* Healthcare and Healing Gardens: Designing therapeutic landscapes for hospitals, hospices, and care facilities that promote healing, reduce stress, and provide restorative environments for patients and staff.

* Educational Campuses: Designing outdoor learning environments, recreational areas, and aesthetic landscapes for schools and universities.

* Retail and Mixed-Use Developments: Creating inviting public spaces, plazas, and pedestrian links that enhance the commercial appeal and overall experience of shopping and entertainment districts.

D. Ecological and Environmental Design:

* Wetland Restoration: Designing and implementing projects to restore degraded wetlands, enhancing biodiversity, improving water quality, and providing flood control.

* Stormwater Management: Designing green infrastructure solutions (rain gardens, bioswales, permeable pavements) to manage stormwater runoff, reduce urban flooding, and replenish groundwater.

* Coastal Resilience: Designing adaptive landscapes and protective measures (e.g., living shorelines) to mitigate the impacts of sea-level rise and coastal erosion.

* Habitat Restoration: Recreating or enhancing natural habitats to support specific plant and animal species, contributing to biodiversity conservation.

* Landfill Reclamation and Brownfield Redevelopment: Transforming former industrial sites, mines, or landfills into productive and ecologically valuable landscapes (e.g., parks, recreational areas).

E. Regional and Urban Planning:

* Master Planning: Developing comprehensive plans for large-scale developments, urban districts, or entire regions, integrating open space networks, transportation systems, and land use.

* Green Infrastructure Planning: Strategically planning and implementing interconnected networks of natural and semi-natural areas within a region to provide ecosystem services and enhance resilience.

* Park Systems and Trail Networks: Designing interconnected systems of parks, greenways, and trails for recreation, ecological corridors, and alternative transportation.

The Transformative Impact of Well-Designed Landscapes

The work of landscape architects has far-reaching benefits, impacting not just the beauty of a place but also its ecological health, social vitality, and economic value.

A. Environmental Benefits:

* Climate Change Mitigation and Adaptation: Landscapes can absorb carbon dioxide, reduce urban heat island effects (through tree canopy and green roofs), manage stormwater (reducing flooding), and filter pollutants.

* Biodiversity Conservation: Creating and restoring habitats supports diverse plant and animal life, contributing to ecological health.

* Water Quality Improvement: Green infrastructure naturally filters pollutants from runoff, improving the quality of rivers, lakes, and oceans.

* Air Quality Enhancement: Trees and plants filter air pollutants, contributing to cleaner, healthier urban environments.

* Soil Health and Erosion Control: Proper planting and grading practices prevent soil erosion and promote healthy soil ecosystems.

B. Health and Well-being Benefits:

* Physical Activity: Parks, trails, and active recreation spaces encourage walking, running, cycling, and play, contributing to physical health.

* Mental Health: Access to green spaces has been shown to reduce stress, improve mood, enhance cognitive function, and foster a sense of well-being.

* Community Engagement: Public parks and plazas provide venues for social interaction, community events, and cultural activities, strengthening social ties.

* Restoration and Healing: Therapeutic gardens in healthcare settings offer calming and restorative environments for patients, families, and caregivers.

* Improved Air and Water Quality: Direct benefits to human respiratory and overall health from cleaner environments.

C. Economic and Social Benefits:

* Increased Property Value: Well-designed landscapes and proximity to green spaces can significantly increase property values.

* Attracting Investment: High-quality public spaces and green infrastructure can attract businesses and residents, stimulating economic development.

* Tourism and Recreation: Iconic parks and designed landscapes become major tourist attractions, boosting local economies.

* Reduced Infrastructure Costs: Green infrastructure solutions can be more cost-effective than traditional “gray” infrastructure for managing stormwater, often providing multiple co-benefits.

* Placemaking: Creating distinct, memorable, and beloved places that foster a strong sense of community identity and pride.

* Social Equity: Ensuring access to quality green spaces for all communities, particularly in underserved urban areas, promotes environmental justice and equitable access to vital resources.

Challenges and Future Horizons for Landscape Architecture

Despite its critical role, the profession faces evolving challenges, particularly in the context of climate change and rapid urbanization. Yet, these challenges also open new frontiers for innovation.

A. Current Challenges:

* Climate Change Impacts: Designing landscapes that are resilient to increasingly extreme weather events, sea-level rise, and altered growing conditions. This requires new approaches to materials, planting, and water management.

* Urbanization and Density: Balancing the need for green space with the pressures of increasing urban density and limited land availability.

* Funding and Implementation: Securing adequate funding for large-scale public landscape projects and ensuring their long-term maintenance.

* Policy and Regulation: Navigating complex planning regulations, zoning laws, and environmental policies that can sometimes hinder innovative landscape solutions.

* Public Perception and Awareness: Elevating public understanding of landscape architecture’s breadth and critical role beyond mere decorative gardening.

* Technological Integration: Effectively integrating new technologies (smart sensors, drones, AI) into landscape analysis, design, and management.

B. Emerging Trends and Future Directions:

* Climate-Positive Design: Moving beyond sustainability to designs that actively sequester carbon, generate renewable energy (e.g., solar integration in hardscape), and improve ecological health.

* Nature-Based Solutions (NBS): Increasingly using natural processes and ecosystems (e.g., wetlands for wastewater treatment, urban forests for air purification) to address complex environmental and societal challenges.

* Bio-Inclusive Design: Creating landscapes that are not just human-centric but actively designed to support and enhance biodiversity, integrating wildlife habitats into urban and suburban environments.

* Smart Landscapes: Integrating sensors, IoT devices, and data analytics into landscapes for real-time monitoring of water use, plant health, air quality, and public safety, enabling adaptive management.

* Community Co-Design and Engagement: Greater emphasis on involving local communities in the design process to ensure landscapes truly meet their needs and foster ownership.

* Restorative Urbanism: Focusing on transforming degraded urban environments into thriving, ecologically functional, and socially vibrant spaces.

* Digital Fabrication and Advanced Materials: Utilizing new manufacturing techniques and innovative materials (e.g., permeable pavements, recycled composites) to create more durable, sustainable, and aesthetically diverse landscapes.

* Landscape as Infrastructure: Recognizing and planning landscapes not just as amenities, but as essential green infrastructure that provides critical ecosystem services for cities and regions.

* Therapeutic and Biophilic Design: Further incorporating principles of biophilia (human innate connection to nature) into all types of landscapes to enhance human health, well-being, and cognitive function.

Conclusion

Landscape architecture is a dynamic and essential force in shaping the world around us. It’s an intricate dance between art and science, leveraging deep ecological knowledge, creative design principles, and a profound understanding of human interaction to transform outdoor spaces. From the historical grandeur of formal gardens to the contemporary urgency of climate-resilient urban parks, the profession continually adapts to societal needs and environmental imperatives. The work of crafting outdoor spaces transcends mere aesthetics; it’s about fostering healthier communities, protecting vital ecosystems, and building more resilient, beautiful, and livable environments for future generations. As we face increasingly complex global challenges, the foresight and ingenuity of landscape architects will be more critical than ever in defining the quality of our shared outdoor experience.