Baroque architecture, an extraordinary and influential style that dominated Europe from the early 17th to mid-18th centuries, represents a dynamic shift from the classical restraint of the Renaissance to a world of heightened emotion, dramatic grandeur, and theatricality. Far from being merely ostentatious, Baroque grandeur was a powerful artistic expression that aimed to evoke awe, inspire devotion, and showcase the might of both the Church and absolute monarchies. Its characteristic features—undulating forms, opulent decoration, illusionistic effects, and a pervasive sense of movement—revolutionized architectural design, creating spaces of unparalleled spiritual and visual impact. Exploring its enduring legacy reveals a complex interplay of art, power, and faith that continues to captivate and inspire.

The Genesis of Extravagance

Baroque architecture did not emerge in a vacuum; it was a direct evolution and reaction to the principles of the Renaissance. While the Renaissance emphasized balance, harmony, and classical order, the Baroque sought to break free from these constraints, embracing dynamism, emotion, and spectacular effects.

A. Renaissance Foundations (14th-16th Centuries):

* Characteristics: Renaissance architecture, exemplified by figures like Brunelleschi and Palladio, was marked by a rediscovery of classical Roman and Greek principles. It valued symmetry, proportion, clear geometry, and often a sense of calm and rationality.

* Influence of the Dome: The monumental dome of St. Peter’s Basilica, completed during the Renaissance, served as a precursor to the grand scale and spatial complexity that Baroque architects would later embrace.

* Limitations: While elegant, the perceived rigidity and intellectualism of late Renaissance style left room for a more emotional and persuasive architectural expression.

B. The Counter-Reformation’s Impetus (Mid-16th Century onwards):

* Religious Turmoil: The rise of the Protestant Reformation in the 16th century profoundly challenged the authority of the Catholic Church. This led to the Counter-Reformation (or Catholic Reformation), a vigorous response to reassert Catholic dominance and attract followers.

* Art as Propaganda: The Council of Trent (1545-1563) recognized the powerful role of art and architecture in religious instruction and emotional persuasion. It called for art that was clear, intelligible, and above all, emotionally compelling and dramatic, to inspire devotion and counter the austerity of Protestantism.

* Jesuit Influence: The Society of Jesus (Jesuits), founded in 1540, became a key vehicle for the Counter-Reformation. Jesuit churches, like the Gesù in Rome, were among the first to experiment with Baroque elements, emphasizing a grand, unified space designed to focus attention on the altar and overwhelm the senses with spiritual experience.

C. Absolute Monarchy and State Power (17th-18th Centuries):

* Consolidation of Power: The 17th century saw the rise of powerful absolute monarchs across Europe (e.g., Louis XIV in France, the Habsburgs in Austria). These rulers used art and architecture as instruments to demonstrate their divine right, wealth, and power.

* Grand Palaces and Royal Residences: Palaces like Versailles in France or Schönbrunn in Austria became prime examples of Baroque’s application to secular power, designed to impress, entertain, and control courtiers, reflecting the grandeur of the state.

* Urban Planning: Baroque principles extended to urban planning, creating grand avenues, monumental squares, and coordinated facades to reflect the order and power of the state (e.g., Bernini’s Piazza San Pietro in Rome).

D. Technological Advancements and Artistic Freedom:

* New Construction Techniques: While not a radical structural break from Renaissance, Baroque architects pushed existing construction techniques to new limits, enabling more complex curves, domes, and theatrical effects.

* Material Exploration: Extensive use of rich materials like marble (often multi-colored), stucco, bronze, and gilding to create dazzling surfaces.

* Integration of Arts: Baroque architects often collaborated closely with painters, sculptors, and decorators, creating a Gesamtkunstwerk (total work of art) where architecture, sculpture, and painting merged seamlessly to create immersive environments.

The Elements of Baroque Drama

Baroque architecture is characterized by a set of dynamic and elaborate features designed to create a sense of movement, drama, and emotional impact.

A. Emphasis on Movement and Drama:

* Curvilinear Forms: A radical departure from Renaissance straight lines, Baroque architecture embraced undulating walls, convex and concave facades, and oval plans (e.g., Borromini’s San Carlo alle Quattro Fontane). This created a dynamic, flowing sense of movement that draws the eye.

* Undulating Facades: Facades were often designed to project and recede, creating a sculptural effect and a sense of theatricality, as if the building itself were alive.

* Dramatic Contrasts: Strong contrasts between light and shadow (chiaroscuro), rich and simple materials, and open and enclosed spaces to heighten emotional intensity and visual excitement.

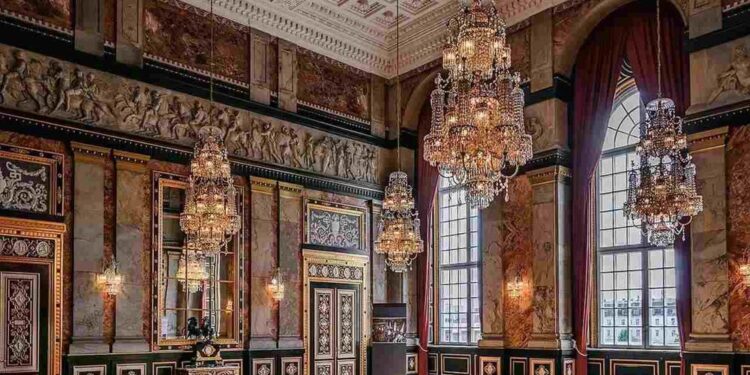

B. Rich and Opulent Decoration:

* Extensive Ornamentation: Surfaces were heavily adorned with elaborate carvings, stucco work, frescoes, and gilded details, often overwhelming the viewer with sensory richness.

* Multi-Colored Marbles: Extensive use of different colored marbles, often highly polished, to create luxurious and visually complex interiors.

* Gilding: Generous application of gold leaf to architectural elements, sculptures, and frescoes, adding brilliance and emphasizing divine light.

* Illusionistic Frescoes: Ceilings were often painted with trompe l’oeil (deceive the eye) frescoes, creating the illusion of open skies, soaring figures, and infinite space, blending architecture and painting seamlessly (e.g., ceiling of the Church of the Gesù).

C. Grand Scale and Monumentality:

* Imposing Size: Baroque buildings were typically large and imposing, designed to inspire awe and convey the power of the institutions they represented (Church or monarchy).

* Grand Staircases: Elaborate, multi-flight staircases became a key feature, serving not just as circulation elements but as ceremonial spaces for dramatic entrances and processions (e.g., Schönbrunn Palace).

* Colossal Orders: Use of giant pilasters or columns that span multiple stories, creating a sense of overwhelming scale and unity on facades.

D. Integration of Arts (Gesamtkunstwerk):

* Unified Artistic Experience: Architecture, sculpture, painting, and sometimes music and theater were conceived as a single, unified artistic experience. Sculptures often burst from walls, paintings extended into architectural elements, and lighting was carefully controlled.

* Theatricality: The overall effect was designed to be highly theatrical, engaging the emotions of the viewer and creating an immersive, dramatic experience, particularly within churches where the intention was to inspire spiritual ecstasy.

E. Symbolism and Allegory:

* Religious Iconography: Churches were replete with symbolic imagery, allegorical figures, and narratives from the lives of saints and biblical events, serving as visual sermons.

* Secular Symbolism: Palaces often incorporated mythological figures, heroic narratives, and symbols of the monarch’s power and virtues.

F. Centralization and Dominance of the Dome:

* Centralized Plans: While basilican plans remained common for churches, there was a greater experimentation with centralized plans (often oval or Greek cross) and the dramatic use of domes.

* Prominence of the Dome: Domes became key features, often elaborately decorated with frescoes that dissolved the architectural boundaries, drawing the eye upwards towards a perceived heaven. They served as a crowning glory, visible from afar.

Baroque Across Europe

While originating in Italy, Baroque architecture spread across Europe, adapting to local tastes, materials, and religious or political contexts, resulting in diverse regional styles.

A. Italian Baroque (The Genesis):

* Characteristics: The birthplace of Baroque, characterized by its dynamism, dramatic light, and integration of painting and sculpture. Figures like Bernini and Borromini pushed the boundaries of form and space.

* Key Figures:

* Gian Lorenzo Bernini: Master of sculpture, architecture, and urban planning. Known for the colonnades of St. Peter’s Square, the Baldacchino within St. Peter’s, and the Cornaro Chapel (Ecstasy of St. Teresa) – a perfect example of Gesamtkunstwerk.

* Francesco Borromini: Known for his highly innovative and complex curvilinear forms, manipulating space in unprecedented ways (e.g., San Carlo alle Quattro Fontane, Sant’Ivo alla Sapienza).

* Examples: St. Peter’s Basilica (its final Baroque elements), Il Gesù, Sant’Andrea al Quirinale.

B. French Baroque (Classical Baroque):

* Characteristics: A more restrained and classical form of Baroque, less overtly dramatic than Italian Baroque, emphasizing grandeur, order, and formality. It served primarily as a tool of royal power.

* Key Figures: Louis Le Vau, Jules Hardouin-Mansart (architects), André Le Nôtre (landscape architect).

* Examples: Palace of Versailles (the quintessential French Baroque palace), Les Invalides, Louvre Palace extensions. Features include vast symmetrical plans, grand axes, and harmonious proportions.

C. Spanish Baroque:

* Characteristics: Often characterized by intense ornamentation, especially on altarpieces (retablos), and a strong religious fervor. Plateresque (silver-like) and Churrigueresque (highly ornate, intricate) styles emerged.

* Examples: Santiago de Compostela Cathedral (Baroque façade), various churches and palaces in Madrid and Seville. Often combined with Mudéjar (Moorish) influences.

D. Austrian and Central European Baroque:

* Characteristics: Highly decorative, joyful, and often light-filled, frequently incorporating pastel colors and stucco work. Used extensively for monasteries, churches, and imperial palaces.

* Key Figures: Johann Bernhard Fischer von Erlach, Johann Lukas von Hildebrandt.

* Examples: Schönbrunn Palace (Vienna), St. Charles Borromeo Church (Vienna), Melk Abbey. This style spread into Germany and Eastern Europe.

E. English Baroque:

* Characteristics: More restrained than continental Baroque, often blending Baroque elements with classical and Palladian influences. Christopher Wren was the dominant figure.

* Key Figures: Sir Christopher Wren, Sir John Vanbrugh, Nicholas Hawksmoor.

* Examples: St. Paul’s Cathedral (London), Blenheim Palace, Castle Howard. Known for grand scale and imposing presence, but with less overt emotionality.

F. Other Regional Expressions:

* Portuguese Baroque: Distinctive for its use of gilded woodcarving (talha dourada) and azulejos (painted ceramic tiles).

* Latin American Baroque: Transplanted to the Spanish and Portuguese colonies, it evolved into a highly exuberant and often syncretic style, blending European forms with indigenous artistic traditions and materials, resulting in churches and public buildings of incredible richness and local character.

Construction and Craftsmanship

Building Baroque masterpieces required not only visionary design but also advanced engineering, skilled craftsmanship, and vast resources, pushing the boundaries of construction for their time.

A. Masonry and Structural Innovation:

* Load-Bearing Walls and Piers: While seemingly complex, Baroque buildings still primarily relied on thick masonry walls, large piers, and arches to bear loads. The innovation lay in how these elements were shaped and articulated.

* Dome Construction: The construction of massive domes, often with elaborate internal and external shells, required sophisticated engineering and scaffolding techniques. Architects like Bernini and Borromini were masters of this.

* Complex Geometries: The curvilinear and undulating forms demanded precise cutting and fitting of stone and brick, pushing the limits of traditional masonry.

B. Materials and Finishes:

* Marble: Extensive use of marble, often imported from distant quarries, for floors, walls, columns, and sculptural elements. Different colors were used to create striking contrasts and patterns.

* Stucco and Plaster: Highly malleable materials used to create elaborate decorative elements, garlands, putti, and figures, often painted and gilded to resemble stone or metal.

* Fresco Painting: Techniques for painting directly onto wet plaster ceilings and walls to create vast, immersive, and illusionistic scenes, often dissolving the architectural boundaries.

* Gilding: The application of gold leaf to wood, stucco, and metal to add luminosity and emphasize the richness and divine nature of the spaces.

* Bronze: Used for monumental sculptures, altar elements, and decorative details, often gilded.

C. Skilled Artisans and Workshops:

* Integration of Trades: Architects worked closely with legions of highly skilled masons, sculptors, painters, carvers, and metalworkers. Large workshops were established to produce the intricate decorative elements.

* Master-Apprentice System: Knowledge and techniques were passed down through generations within artisan guilds.

* Project Management: The sheer scale of Baroque projects required sophisticated project management to coordinate hundreds or even thousands of laborers and artisans over many years.

D. Theatricality and Light Control:

* Hidden Light Sources: Architects often employed clever techniques to introduce light from unseen sources (e.g., hidden windows, oculus within domes) to illuminate sculptures or altars dramatically, enhancing the sense of divine intervention or mystical presence.

* Staging and Progression: Interiors were designed to guide the visitor through a carefully orchestrated sequence of spaces, building up to climactic moments (e.g., the high altar, a grand hall).

Controversies and Modern Interpretations

Baroque architecture, despite its historical importance, has often been subject to criticism, but it continues to fascinate and influence.

A. Historical Criticisms and Decline:

* “Excessive” and “Overly Ornate”: During later periods (e.g., Neoclassicism), Baroque was criticized for its perceived excess, lack of restraint, and departure from classical purity, often labeled as “decadent.”

* Cost and Labor: The immense resources required for Baroque construction contributed to its decline as tastes and economic priorities shifted.

* Association with Monarchy and Absolutism: Its strong ties to absolute monarchs and the Counter-Reformation sometimes made it unpopular during periods of democratic or revolutionary fervor.

B. Modern Reappraisals:

* Re-evaluation of Art History: 20th-century art historians began to re-evaluate Baroque not as a decline from the Renaissance, but as a distinct and powerful artistic movement with its own aesthetic logic and expressive power.

* Psychological Impact: Modern studies recognize the deliberate psychological impact of Baroque design, its ability to engage emotions, and its skill in creating immersive environments.

* Influence on Later Movements: Elements of Baroque dynamism and theatricality can be seen influencing later architectural styles, including Rococo, and even elements of 20th-century Expressionism or Postmodernism.

* Urban Context: Appreciation for its urban planning contributions, particularly the creation of grand public squares and avenues.

C. Preservation and Tourism:

* Conservation Challenges: The intricate ornamentation, delicate stucco work, and large-scale frescoes of Baroque buildings require continuous and specialized conservation efforts.

* Massive Scale: The sheer size of many Baroque churches and palaces makes their maintenance a constant financial and logistical challenge.

* Tourism Magnets: Baroque sites like St. Peter’s Basilica, Versailles, and Schönbrunn Palace attract millions of tourists annually, making them crucial cultural and economic assets.

* UNESCO World Heritage Sites: Many Baroque masterpieces are recognized as UNESCO World Heritage Sites, signifying their outstanding universal value and warranting international protection.

D. Contemporary Influence (Subtle):

* Theatricality in Design: Modern architects and designers might draw inspiration from Baroque’s use of drama, light, and movement to create impactful spaces, particularly in public buildings, museums, or entertainment venues.

* Complexity and Multi-Sensory Experience: A renewed interest in designing spaces that engage multiple senses and offer complex, layered experiences, reminiscent of the Baroque Gesamtkunstwerk.

* Sculptural Forms: The boldness and sculptural quality of Baroque architecture can be seen as a precursor to some highly expressive forms in contemporary architecture.

Conclusion

Baroque architecture, a magnificent testament to human ambition and artistic fervor, stands as a triumph of drama, grandeur, and emotional impact. From its origins in Counter-Reformation zeal and the assertion of absolute monarchical power, it broke free from the classical norms of the Renaissance to embrace undulating forms, lavish ornamentation, and breathtaking illusionistic effects. Whether in the dynamic facades of Borromini, the monumental colonnades of Bernini, or the opulent halls of Versailles, grandeur and drama permeated every aspect of its design. While often critiqued for its excess, its profound influence on urban landscapes, its innovative construction, and its ability to inspire deep emotional responses remain undeniable. As we continue to study and preserve these spectacular structures, Baroque architecture serves as a timeless reminder of an era when art, power, and faith converged to create some of the most compelling and awe-inspiring spaces ever conceived.